Handling Medieval Meat

I hope all is well! What’s new with you?

I’m in Paris this week on a short trip, it’s been a long time since I grabbed hold of a baguette with both hands.

By the way, it is "Paris" with an 'S', not “Pari”. Affected pronunciations are not the done thing. The same would apply to "chorizo" in Spanish or rolling your 'R's in "mozzarella" in Italian. Doing so is fundamentally common.

I’m not alone in this pronunciation pet peeve it turns out! There was broad agreement among us all about my and Jordan’s guest appearance on Dish a fortnight ago.

Medieval meat: habits and history

Nowadays, as you may have seen here, removing some gristle off your meat and discarding it with decorum is what we want and expect in 21st-century dining, but how was it back in the days of banquets and feasts in castles? How similar is modern dining to medieval dining?

Christmas feast in the Middle Ages

Dispelling modern myths

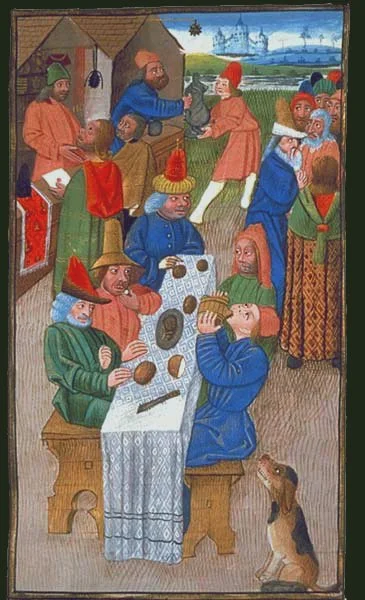

Like the painting above, the words medieval and banquet conjure up images of gout-ridden kings who ate meat and rich food all day long for their own greed while the peasants beyond the castle frontiers starved.

Bioarcheologists and historians publishing in Anglo-Saxon England found when reading compilations of food lists that,

“The scale and proportions of these food lists strongly suggests that they were provisions for occasional grand feasts, and not general food supplies sustaining royal households on a daily basis. These were not blueprints for everyday elite diets as historians have assumed.”

Having said that, it is generally true that the rich ate better, but only a bit later on. Once the Black Death wiped out a third of the European population in the 14th century, the food supply became rapidly abundant with fewer mouths to feed, only then did monarchs eat like kings.

No wonder Henry VIII piled on the girth.

Pieter Claesz: Still Life with Peacock Pie, 1627

The takeaway tavern?

Even in bustling towns and cities, not everyone had the luxury of a home-cooked meal. Enter the medieval takeaway. Public kitchens dished out warm meals to hungry travellers and locals alike, a precursor to our modern fast-food joints. Compared to the quality of them, a medieval munch does not sound all too bad.

Medieval manners

You may have heard me say that you never cut into bread with a knife because bread is broken with the hands. Centuries ago, you would use your personal knife (the knife you used for living and killing animals etc) for meat only, keeping the bread free of blood.

Upon entry to a feast, your personal knife was sharpened against a whetstone, hence the saying to whet one’s appetite!

A medieval banquet, complete with peacock, mid-15th century.

I'm overwhelmed with the enthusiasm and support you have shown for my upcoming book! So once again, thank you.

Yours in culinary exploration,

William Hanson